The following is a brief analysis by Krista Swanson, the lead economist for the National Corn Growers Association.

The recent banking fallout and economic comparisons to the 1980s are likely to grab the attention of anyone in agriculture. Fortunately, the general economic environment and financial positioning of farmers is quite different than that period. Here is a look at three key points, with data to assess the current conditions as compared to the 1980s.

Highest Farm Debt Since 1980, But Stronger Farm Solvency

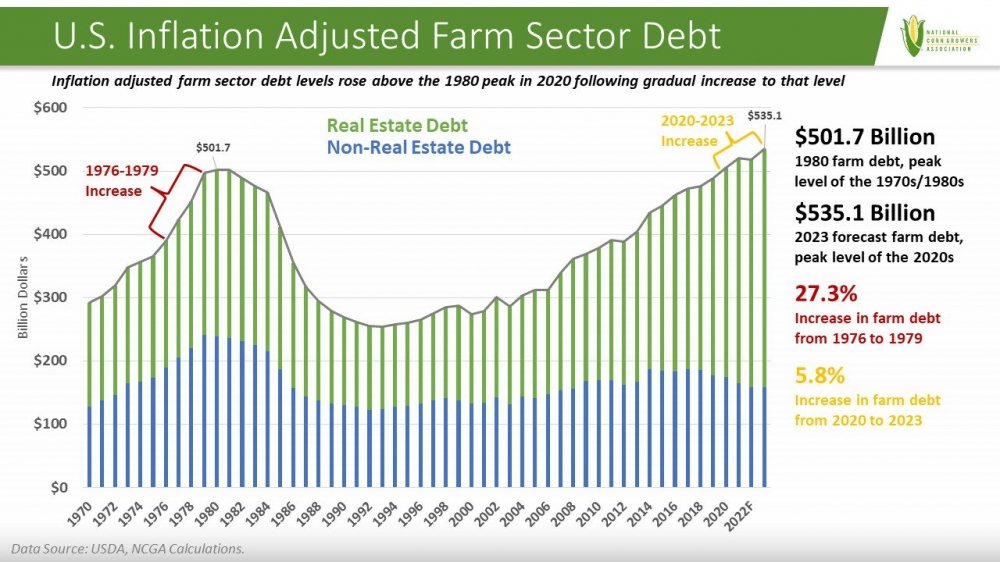

The USDA has forecast total real (inflation adjusted) farm debt at $535.1 billion for 2023, continuing what has been a relatively steady upward trend throughout the 2000s. Up until 2020, farm debt remained below the 1980 inflation adjusted peak of $501.7 billion. Since 2020, farm debt levels have been higher, but near the peak points of the earlier era. The comparison of today’s farm debt levels to 1980 may be concerning, but other important values differ.

In the 1980s, real estate accounted for only half of total farm debt. For 2023, real estate accounts for 70% of total farm debt. Current high debt levels are more concentrated in real estate debt backed by high value and generally stable farm assets, particularly farmland. Additionally, farm debt of the earlier era accrued rapidly, jumping 27.3% from 1976 to 1979. In contrast, farm debt levels have risen 5.8% from 2020 to 2023, consistent with the gradual growth pace over the past two decades.

The current farm sector solvency is notably stronger than the 1980s. For 2023, the farm sector debt-to-asset ratio is forecast at 13.22, stronger than the 1985 peak at 22.19. Likewise, the farm sector debt-to-equity ratio is forecast at 15.24 for 2023, stronger than the 28.51 peak in 1985.

While comparisons between today’s farm debt levels and the 1980s can be drawn, relative strength in farm assets and farm solvency contrasts with the earlier era, and indicates farmers today are better positioned to maintain and pay down relatively equivalent levels of debt.

Highest Inflation Since 1981, But Lower Interest Rates

The Consumer Prices Index (CPI), a common measure of inflation, hit 9.1% in June 2022, reaching the highest point since 1981. Generally noted causes for inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s are the oil crisis of the era, government overspending, and a cycle of higher wages and higher prices. Meanwhile, factors often attributed to the current period of inflation are the COVID shutdown related supply chain disruptions and the post-shutdown high level consumer savings and pent-up consumer demand. Though often overlooked, what may be the most important contributing factor to current inflation is the more than 40% increase in money supply from 2020 to 2022, as the Federal Reserve used quantitative easing to push the economy out of the short but severe 2020 recession.

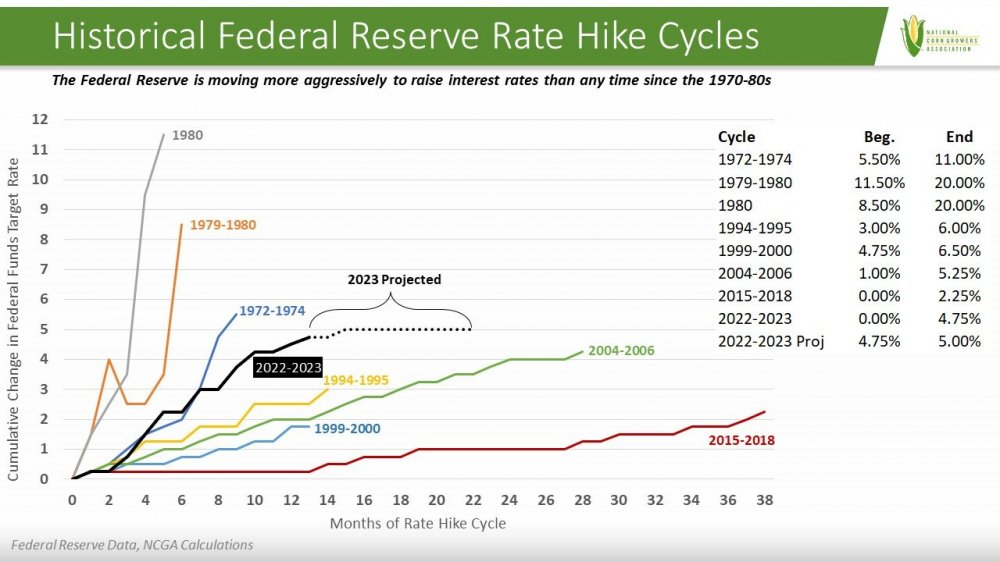

Importantly, it took the Federal Reserve raising the federal funds rate to a high point of 20% in 1980 to control inflation of that era. Including the first rate increase in March 2022, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates nine times to the current federal funds rate range of 4.75% to 5%. Inflation has dropped from the 9.1% high to 6.0% in the most recent CPI. Although inflation is not yet back to the 2% target rate, inflation has declined in the higher interest rate environment. Notes released after the March 2022 meeting of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee indicate the end of the rate hike cycle is near.

While comparisons between recent inflation levels and the 1980s can be drawn, current interest rates are merely one quarter of the peak rate of that era and further increase is likely to be minimal.

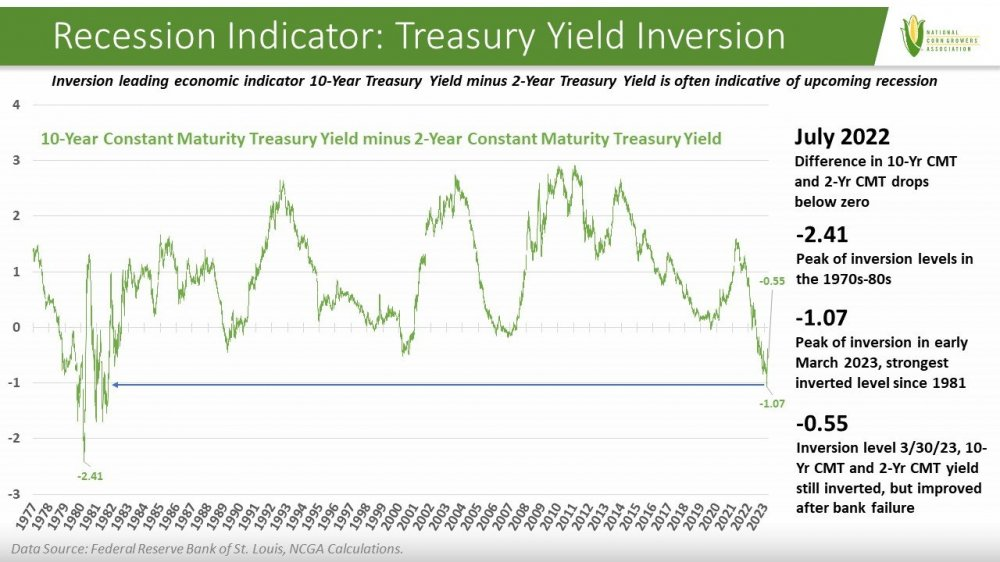

Highest Treasury Bond Inversion since 1981, But Production Agriculture Better Positioned

Several economic indicators point toward impending recession. One indicator, the relationship between 2-year treasury bond yields and 10-year treasury bond yields, has received added attention amid recent bank failures because the inversion in yields of these two treasury bonds challenges banks who rely on the normal positioning of lower short-term rates and higher long-term rates. This normal relationship makes sense, a greater risk would be expected when committing money for a longer period. An inversion means the opposite is true, with higher short-term rates and lower long-term rates. When that has happened in the past, a recession within two years has occurred 98% of the time. This indicator has accurately predicted the last eight recessions. The two treasury yields inverted last summer, but in early March the inversion was at the widest position since 1981. Since the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, the inversion has narrowed some, but it still points toward recession.

For farmers, the notion of a forthcoming recession and comparisons to the 1980s triggers thoughts of the 1980s farm economic crisis. While inflation and interest rates played a part in that, a multitude of other factors led to that outcome. If the U.S. moves into recession over the next year, production agriculture enters it better positioned than coming into the 1980s and could continue to remain strong and resilient, particularly if the recession is short. Although production agriculture runs in a race with the rest of the economy, it doesn’t always follow the same course. Other factors impacting production agriculture are economic conditions of trade partners and other producers, the value of the dollar related to other currencies, weather, geopolitical relationships, and policy related to agriculture.

For more on the Silicone Valley Bank Failure, inflation, and interest rates listen to this recent Cobcast episode.